I promised awhile back to bore you with a description of engine leaning procedures in airplanes. This is a good time for those yawning to move on to another topic. But if you are interested, stick with me.

The concept is pretty simple. In an engine, the mixture of fuel and air is just as important as it is in your fireplace. The engine leaning control adjusts the mixture, or the ratio of fuel to air going into the cylinders, and it is particularly important in airplanes because as you increase altitude, there is less barometric pressure to push air into the engine, and the air is less dense (or thinner) so it has less oxygen to burn. So as you increase in altitude, leaning is needed to adjust the amount of fuel in the mixture to match the reduced air pressure and oxygen to give you the desired mixture.

The point is to lower the ratio of fuel to air in the mixture to get to the best setting for your engine at the density altitude and temperature at which you are flying. Pulling the mixture back to full lean will cut off all fuel and stop the engine. As a matter of fact this is exactly how you shut down your engine after you have landed. Pushing the mixture lever to full rich typically gives it a mixture of something like six parts air to one part fuel, and this is set for the particular engine to give a mixture as rich as possible without much loss of power, and to provide enough fuel to cool the engine the most when it is at full takeoff power.

If you climb up to altitude in a plane, level off, and begin to pull the mixture lever back from full rich toward lean, the temperature of the exhaust gas coming out of each cylinder will begin to increase as the fire gets hotter. If you continue leaning, the exhaust gas temperature (EGT) will peak, and then will begin to decline as the mixture moves toward being too lean. Modern planes often have guages that allow you to see the EGT for each cylinder and watch this process unfold, and without specially tuned fuel injectors, the point where each cylinder will hit peak EGT will be different.

Everything I’ve told you so far is factually correct, I think, but when you move on to the question of how to lean an engine at altitude, you enter the realm of superstition and strongly held beliefs among pilots and mechanics, and it is very hard to sort out what is the best setting, and the best method of achieving it. I’m going to start by telling you about the three methods of leaning in order of age, from oldest to newest, and then delve a little into the arguments about exactly how to lean using the newest methods, which are based on instruments not available until late in the 20th century.

The oldest method of leaning is based on the simple proposition that when the mixture gets too lean, it will start to run rough. So the pilot would level off at altitude and then pull back the mixture lever until the engine started running rough. When that occurred, he would push the lever back toward rich until it was smooth again, and that was it. For a long, long time in aviation, this was how engines were leaned, and there are certainly still advocates of this method flying today. It was simple, and it seemed to work, although I find it a little harrowing up there in the sky to be intentionally making my engine run rough.

The second method of leaning came about when instruments were developed which could measure fuel flow. The Pilot’s Operating Handbook for my plane has a guide for such a leaning method, and it amounts to this: If you set the throttle and RPM by the book for 75% power at a certain density altitude, and lean correctly, your fuel flow should be 18.5 gallons Per hour; at 65& power, 16.5 gallons per hour; and at 55% power, 14.5 gallons per hour. Using this method, if you were at 65% power, you would simply lean until you had a fuel flow of 16.5 gallons per hour, and be done with it.

And finally, with probes to measure exhaust gas temperature and cylinder head temperature, first for just one cylinder and now for every cylinder, leaning has truly become an art. We can see the effect on exhaust gas temperatures (EGT’s) within each cylinder and fuel consumption, giving us information that was never available in the past. Oddly, as instruments and measurements have become more precise, there are more arguments today than ever before about how to lean an engine.

When an exhaust gas temperature readout became available, based on one cylinder, the standard leaning method became leaning the mixture until the exhaust gas temperature peaked, and then moving the lever back in the rich direction to somewhere like 100 degrees rich of peak. Later, these guages were replaced by readouts giving the exhaust gas temperatures for every cylinder and the same thing was done with the first cylinder to peak in exhaust gas temperature.

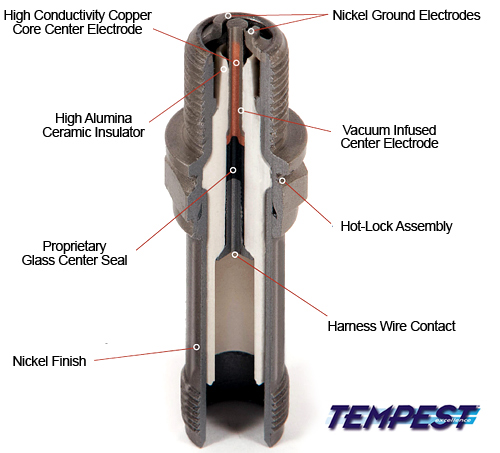

So, what’s the problem? Well, a Company named General Aviation Modifications, Inc., or GAMI, figured out from these modern instruments that cylinders in an aircraft engine, because of how they are placed, get different amounts of air flow. So they invented something called GAMI Injectors which vary the fuel injected into each cylinder to match the air available to the cylinder. The result is that cylinders in one engine behave much more closely alike, and reach peak EGT’s at roughly the same time. With GAMI injectors installed, leaning done the traditional way results in all of the cylinders running pretty much alike.

As the Company says on its website:

GAMIjector® fuel injectors and TurboGAMIjector® fuel injectors are fuel injection nozzles designed to deliver specific amounts of fuel to each individual cylinder that will compensate for the fuel/air imbalance inherent in the fundamental design of the engine fuel/air systems.

Each GAMIjector® fuel injector is carefully calibrated to much tighter tolerances than standard fuel injectors available for your engine. Our award winning GAMIjector® fuel injectors alter the fuel/air ratio in each cylinder so that each cylinder operates with a much more nearly uniform fuel/air ratio than occurs with any standard factory set of injectors.

But GAMI went much further than simply making it possible to get the cylinders all working alike, and began to advocate running engines “lean of peak”, to get better efficiency and cooler cylinder temperatures. A lot of long-time pilots and mechanics scoff at this notion, but over time GAMI has pretty much won the war of convincing everyone that there is a better way to run their aircraft engine. It is now widely accepted that, unless you are operating at very high power settings (higher than 60% to 65% power), it will not hurt an engine to run it at any reasonable leaning position. With GAMI injectors, engines should no longer run rough when somewhere like 50 degrees lean of peak, because all of the cylinders will be behaving close to alike. If you can find a method that keeps the engine cooler and provides best efficiency, that’s what you should use if efficiency and cool cylinders are your goal.

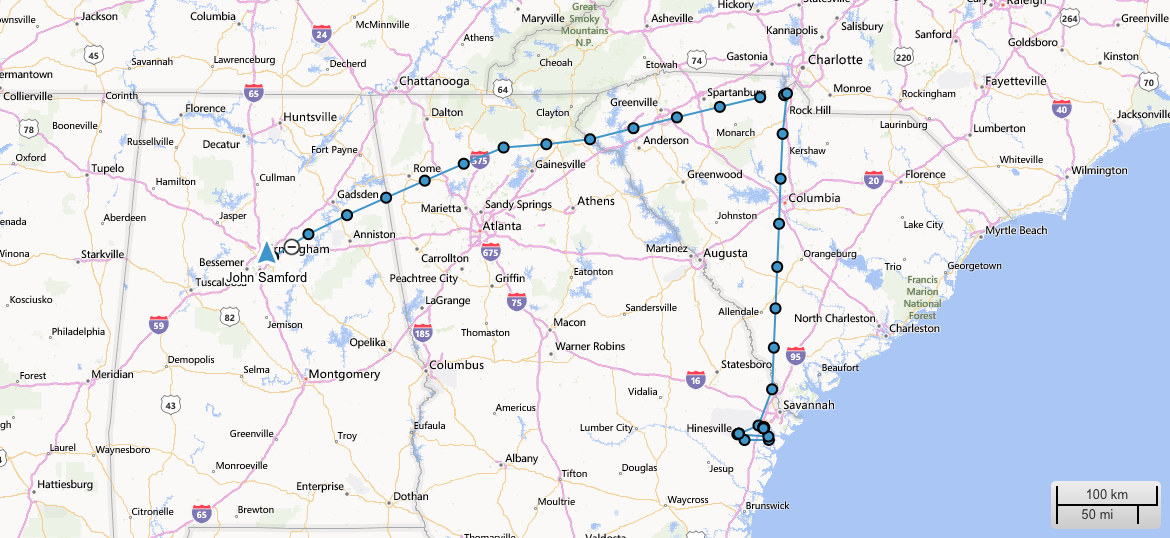

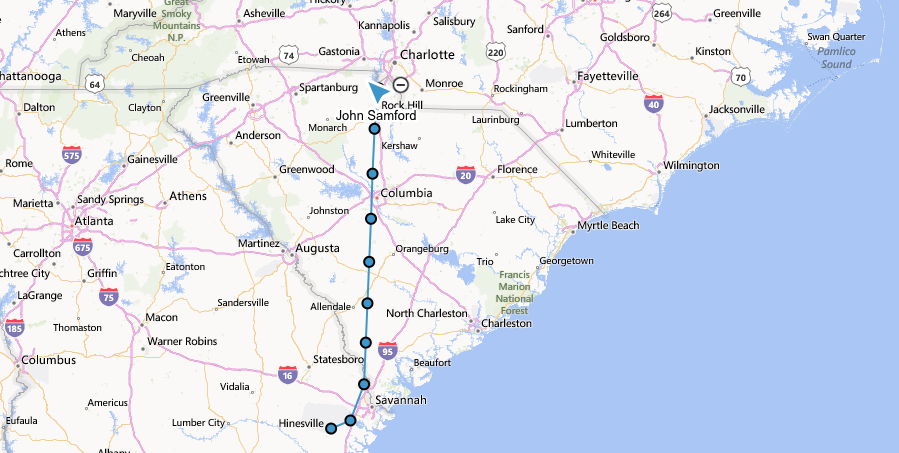

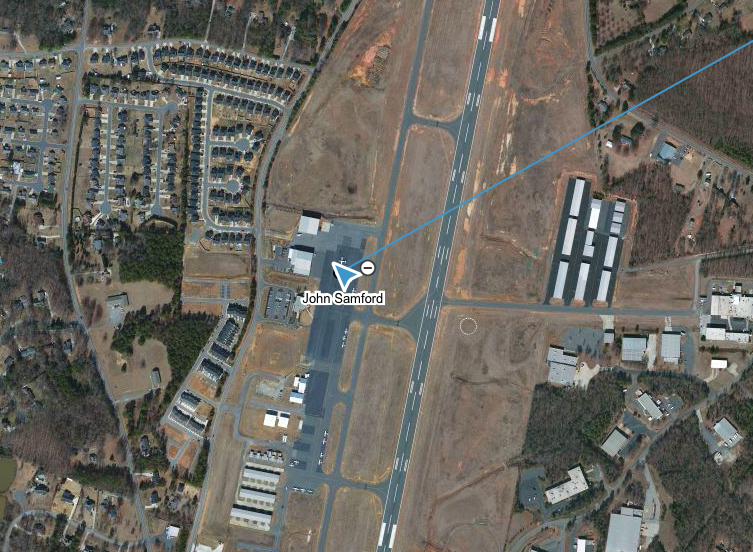

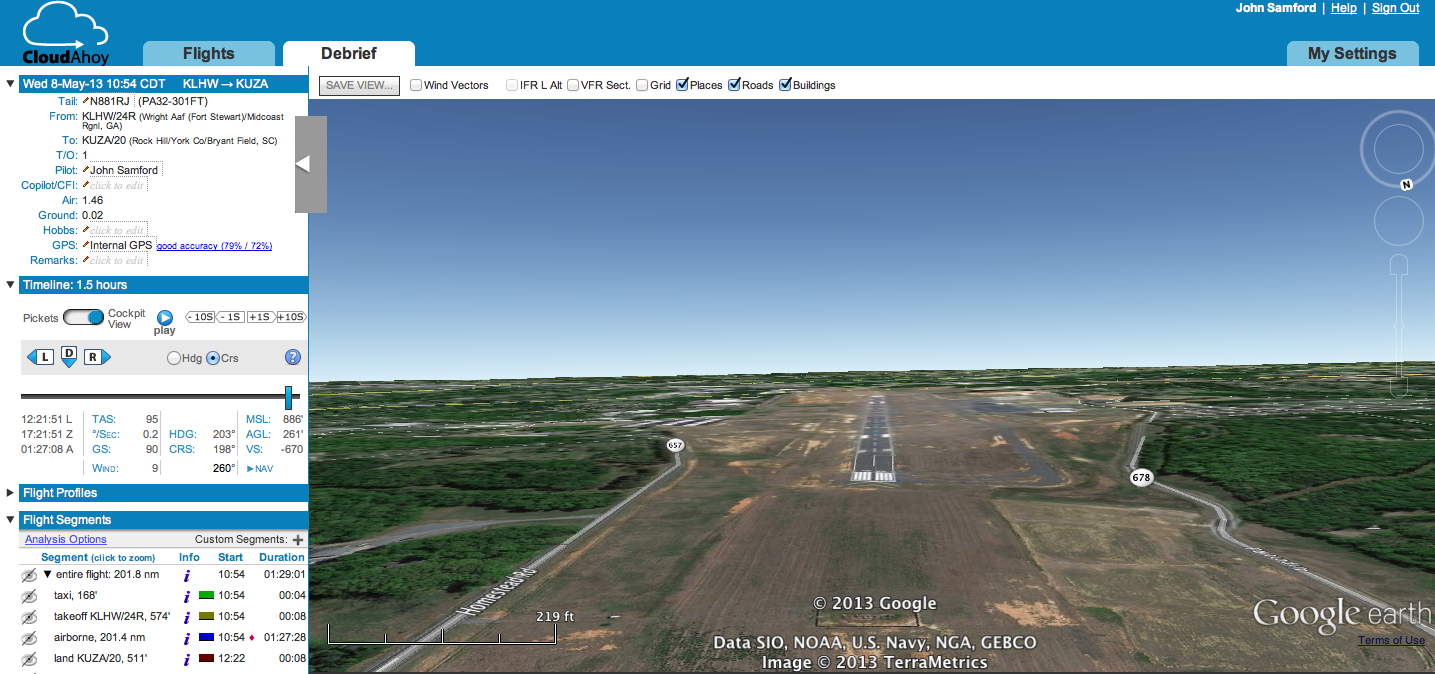

So now I have installed these GAMI’s on my engine, but I have been a little to rattled to go all the way lean of peak so far. The engine is running smoothly, but when I lean back to where most of the cylinders have peaked in exhaust gas temperature, the leaning knob is alarmingly close to the idle shut-off position, and I have been too nervous to pull it back any further. I have been running it about 100 degrees rich of peak at 65% power and burning about 16.5 gallons per hour. I believe my next step will be to try this with an airport below, and an experienced instructor on board, just to make sure I do not kill the engine with nowhere to land while screwing around with the mixture. I’ll keep you posted next time I get a chance to try this out.

The curious thing is that I have had these GAMI injectors in my last two airplanes, and have flown many hours lean of peak. I suppose I am just still getting used to this plane and still a little nervous about trying out new things in it. Meanwhile, I’m probably burning a couple of gallons an hour more than I need to be. I’ll get there though, and I’ll have myself a lean machine soon.

Tuesday, March 3, 2015 at 09:30PM

Tuesday, March 3, 2015 at 09:30PM