Im your captain, Im your captain,

Although Im feeling mighty sick.

Everybody, listen to me,

And return me, my ship.

Grand Funk Railroad

I’m Your Captain

I’ve been in something of a grand funk lately after selling my boat, so I decided to do something nautical last week. Since I started boating in 1990, I’ve wanted to get a Coast Guard Captain’s License. It’s not required on a pleasure boat unless carrying passengers for hire, but it can reduce insurance rates and allow you to bareboat charter easily. And it’s a badge that says you know what you’re doing on the water. Now that I have no ship, it seemed a good time to get the license while my “sea time” is current.

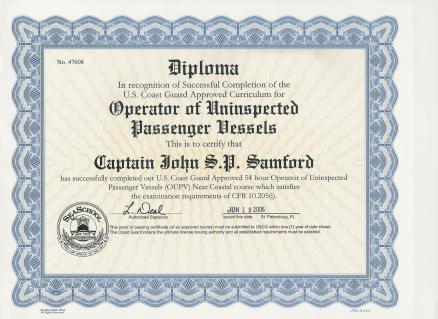

So last week, I drove down to Bayou La Batre, Alabama to attend “Seaschool”. It is a Coast Guard approved 54-hour school aimed at getting the student an “Operator of Uninspected Passenger Vessel” license, also called “OUPV” or “six-pack”, since it allows one to carry up to six passengers.

Bayou La Batre is about 30 minutes south of Mobile along the Mississippi Sound. It looks out across the sound toward Dauphin Island. For years, it has been a center of Shrimping, boatbuilding and boat repair. The area is still devastated from Hurricane Katrina. There are shrimp boats left in the woods from a tidal surge that was 15 feet above land in the area.

Most houses have FEMA trailers parked in their front yards while owners try to get their houses repaired. And there are acres of FEMA trailer parks where families are living in 250 square foot trailers because their houses are simply gone. All of this comes on top of a declining shrimp industry made economically impossible by cheap imported shrimp, high fuel prices, and regulations that are expensive for Shrimpers. A popular bumper sticker I saw in the area says: “Friends don’t let friends eat imported shrimp.” Many of the shrimp boats left in the woods are those whose owners had no insurance, can’t afford to haul them out and couldn’t make money with them if they did salvage them. Amazingly, on the Friday during my week in Bayou La Batre, The New York Times published an article about the area. It is copied below this blog entry..

But while the area tries to recover, jobs are available in the oil fields and on the boats which ferry crews and supplies to the offshore platforms. There are construction jobs rebuilding platforms damaged by Katrina, jobs working the oil rigs, crew boat jobs, and even some privately owned boats are being paid to ferry water and supplies to the oil fields. There are signs along the highway offering $1,000 signing bonuses for licensed 100-ton boat captains who can earn up to $500 a day. So there is a boom of sorts, going on amidst the bust, leading to a full house when Seaschool started class Monday morning.

Our class started at 8 a.m. each morning and ran until 5 p.m. with a one-hour break for lunch. It ran for seven straight days, Monday through Sunday, and finished at 3 p.m. Sunday. It is not necessary to spend that much time in the classroom to go over the material, but the Coast Guard requires the school to run for 54 hours, so it does. We all would have been better off with a little less class and a little more study time. Those continuing through to get the 100-ton Master license continued the class for a total of 10 days while the OUPV candidates finished Sunday and took the four exams Monday. I plan to go back for a three-day school to upgrade to the 100-ton license because I simply couldn’t’t stand 10 straight days of the class.

The class started out with 25 students, but by mid-week, we were down to about 15. Some just decided this wasn’t for them and left after the first day or two. Some learned that they didn’t have the sea time to get the license even if they finished the course. Sadly, it was Wednesday before we got into these details which caused several to drop out. The group of students was extraordinarily diverse, including some fairly rough customers who made a living on oil field supply and crew boats. The language was colorful, to say the least. When I first appeared outside Monday morning, everyone had a cup in his hand which I assumed was coffee. Soon, I discovered that most of the cups were for spitting tobacco juice.

There were three of us, including myself, who were essentially pleasure boaters who might need the license for insurance, to maybe take paying passengers out, or perhaps to hire out to deliver boats. There was a lifelong shrimper who could no longer make a living shrimping and had parked his shrimp boat. He hoped to do some charter fishing trips to earn an income. There was a tugboat captain who already held an “Operator of Uninspected Towing Vessel” License and who wanted to change careers to do fishing charters. He had already passed a much more difficult exam years earlier, but that didn’t help. He could push ten barges loaded with methane gas through the center of New Orleans, but he couldn’t take a group out fishing in the bay for hire.And there were any number of mates or deckhands on oilfield supply and crew boats who wanted to move up to captain where they could increase their earnings.

None of the material we learned was terribly difficult to grasp, although many of the students had barely a high school education and, for them, the mathematics of plotting courses and positions was pretty difficult. Some didn’t know, for example, that a circle has 360 degrees or how to locate a position on the chart when given a latitude and longitude. There was a large amount of memorization of lights and day shapes shown by various types of vessels, fog signals using the horn or “whistle” or a bell, rules of the road, etc.Those with some education had little difficulty with any of it, but I felt for the men who had quit high school 30 years ago, and whose livelihood now depended on their academic skills.

I was struck by one 38-year-old man from Corpus Christi, Texas. He had worked as a deck hand on crew boats, but he did not have a steady job. He had no car and little money, but captains were being hired if he could get the license. He saved up the $900 to pay for the course and rode a bus to Bayou La Batre to attend the school. He appeared totally lost throughout the class. I don’t think he has a prayer of passing the tests, but he doggedly worked through the week. He has the motivation but he’ll have a hard time getting there. I wish him well. He reminded me daily of just how fortunate most of us are.

The school facility was an absolute dump. Our classes were in a basement room with a window unit air conditioner that functioned loudly all week. The chairs were uncomfortable. There were constant distractions. Almost daily during class, the janitor mopped the floors outside our classroom with clorox, leaving many of us gasping. (On Monday, the same janitor graded two of my tests while the regular office manager was at lunch). Several students were staying in “dorm rooms” on the third floor of the building where they could stay free for the week. The floor was more of a barracks and looked as if it hadn’t been cleaned in years.

While the materials and sample questions were excellent and could easily prepare you for the tests, the teaching was awful. Our main teacher did little but read through the written material with us and show how to work a few problems. She ran the class like a drill sargeant and got particularly mad when questions were asked. Often, she simply didn’t know the answer and was mad that she was being put on the spot. If she did know the answer, she was mad that her poor explanations didn’t get through to anyone.

The tests turned out to be easy, and most questions were taken exactly from the sample questions we had been given. I breezed through the four exams starting at 9 a.m. Monday, and by 11:30 I was on the road back to Birmingham. I’m not a captain yet. I have to take a first aid and CPR class, get a physical exam, await the results of the drug test I took at the school, get three character references, and then bundle all of the paperwork together and present it to a Coast Guard regional examination center in Memphis where I can be fingerprinted and issued my license.

The tests turned out to be easy, and most questions were taken exactly from the sample questions we had been given. I breezed through the four exams starting at 9 a.m. Monday, and by 11:30 I was on the road back to Birmingham. I’m not a captain yet. I have to take a first aid and CPR class, get a physical exam, await the results of the drug test I took at the school, get three character references, and then bundle all of the paperwork together and present it to a Coast Guard regional examination center in Memphis where I can be fingerprinted and issued my license.

When it’s all said and done, I’ve asked my wife to address me as “Captain” around the house. She has agreed, as long as I refer to her as “Admiral”.

From The New York Times

June 9, 2006

The Road Back

100-Ton Symbols of a Recovery Still Suspended

By DAN BARRY

BAYOU LA BATRE, Ala., June 7 — To understand a little about this small crustacean of a city nine months after Hurricane Katrina, you have to accept a counterintuitive concept: Boats in the trees.

About two dozen shrimp vessels, some of them 80 feet long and weighing more than 100 tons, list in suspended state amid scrub oak and pine, many yards from the bayou where they belong. Removed from the blue and shoved into the green, their white masts and rigging rise like bleached treetops in a forest.

Here is the Gold Star, rooted in the sand and brush like a huge and dangerous jungle gym. Here is the Peaceful Lady, its charts neatly rolled up inside, its bow planting a hard kiss on a pine. Here is the Mee Mee M, the bottle of soy sauce in its cabin just one of the hints that many of these stranded boats are owned by Vietnamese immigrants.

The only things darting beside the exposed hulls are yellow flies — and shrimp season started Wednesday.

Trying to comprehend the reasons boats still nestle in trees so long after the storm can hurt the brain: the owners never acquired or could not afford insurance; the federal government saw no compelling need to remove them; there are protected wetlands to worry about, and even an Indian burial ground.

If Katrina ever slips momentarily from one’s mind here — if — the plain sight of these boats in the woods snuffs the daydreaming. The slow, complicated efforts to extricate the hurricane-stranded vessels mirror the slow, complicated efforts to extricate this hurricane-damaged city of 2,100 from that one day last August.

“It gets mind-boggling,” said Debbie Jones, 47, who after the hurricane wound up as the city’s long-term recovery coordinator. “I go home at night trying to figure out how we’re going to do this.”

And she was just talking about the boats in the trees.

To get to Bayou La Batre, you turn off U.S. 90 at the Citgo station, where a huge plastic chicken rests in the bed of an El Camino, and follow a road that runs like a stream to the all-important bayou. Shrimp and oysters have long defined the city. But then you pass evidence of Katrina’s temporary redefinition.

The guarded encampment of trailers provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency on Zirlott Park, where children should be playing baseball. The mud-colored tent shading mounds of donated clothing, where, at night, people shine the headlights of cars on the piles as they pick through. The many out-of-state volunteers, including those young Mennonite women along the roadside, playing a game of evening volleyball in their plain dresses and prayer coverings.

These are snapshots from a city where, before the storm, 30 percent of the residents were living in poverty, and rising fuel costs and competition from imports were already squeezing its seafood industry. Life wasn’t easy here, before.

But Bayou La Batre is demonstrating its grit to all “farmers,” as locals refer to anyone who lives inland. Some boat-building continues. Fishing vessels pull in and push out. Heavily damaged St. Margaret’s Roman Catholic Church held a rededication ceremony Sunday morning, and an embroidery class Monday evening. And yet, boats in trees.

Katrina actually stranded several dozen boats, but most of them were insured, which meant their owners were able to pay for their retrieval within a few months. The uninsured vessels are victims of bureaucracy and, simply, the way things are.

A county health officer had the boats declared a public hazard, which prompted the Coast Guard to remove the fuel and batteries, which prompted FEMA to say it no longer had reason to spend public money on retrieving private property, which prompted the state and the city to submit an application to the Clinton-Bush Katrina Fund, a private charity organized by two former presidents.

Finally, two months ago, the city received $1.6 million from the fund to get those boats out of the trees and back into the water. But it seems that no hurricane-related problem is ever easily resolved.

The Army Corps of Engineers, not keen on the idea of dragging tons of steel across protected wetlands, is encouraging salvage crews to take the long way around, along timber cuts, and not straight to the water. And in the case of a few boats some 800 yards into the woods, like the Gulf Star, the shortest path to the bayou might mean disturbing an Indian burial ground.

The Gulf Star’s owner, Jimmy Nguyen, 36, was reached by telephone on a relative’s boat in Mississippi Sound, but he emphasized that he would rather be shrimping out of Bayou La Batre on his own boat, bequeathed to him by a brother. “Most definitely,” he said.

“Your boat looks good, if that helps,” Ms. Jones told him, leaning into a cellphone set on speaker mode. “It hasn’t been vandalized. For the other boats, I can’t say.”

Mr. Nguyen’s thank you came drifting back.

Linked in misery to Mr. Nguyen is Buddy Johnson, 66, the owner of B&B Boat Builders, on the bayou. Katrina took temporary custody of several of his boats, including two shrimp boats he had just bought to refurbish and resell, but which now lay deep in marsh grass, against a pine thicket.

A large man, white, friendly and exceedingly candid, he distinguished himself from everyone else encountered in Bayou La Batre by peppering his observations with slurs about blacks, Catholics and, especially, the Vietnamese. Mr. Johnson, it seems, has a thing about the Vietnamese.

As he stood at the bayou’s edge, some Vietnamese fishermen puttered past, and he said a bad word. Then he returned his gaze to those stranded vessels, a sight that vexed him, a sight that spoke of Katrina’s sweeping democracy.